The Westward Ho pictured in 2018. (Photo: Danny Upshaw)

What does it take to compete for the title of “most interesting building in Phoenix”? Height matters. So does sex appeal and longevity. A spiritual presence is also helpful. Don’t forget celluloid fame and technological innovations. Reshaping the city with your construction debris is an unexpected bonus. One building has all these features and more: the Westward Ho.

The growth of tourism in Phoenix after World War I was the impetus for this swank hotel. The Pacific Hotel Company of Los Angeles planned a 16-story hotel called the “Roosevelt” just north of Downtown Phoenix at Central Avenue and Fillmore Street. Construction began in 1926, but the company went broke before completing the building.

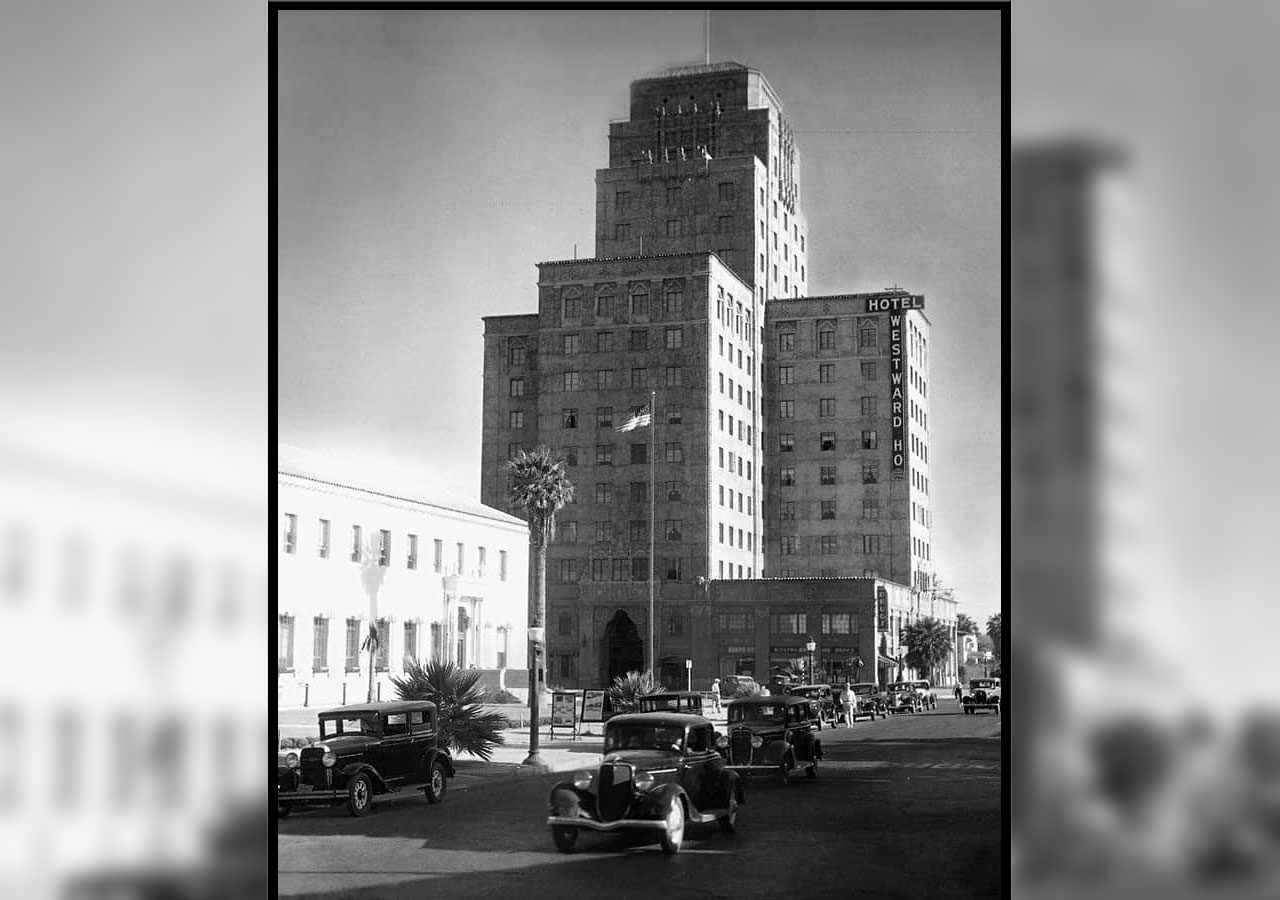

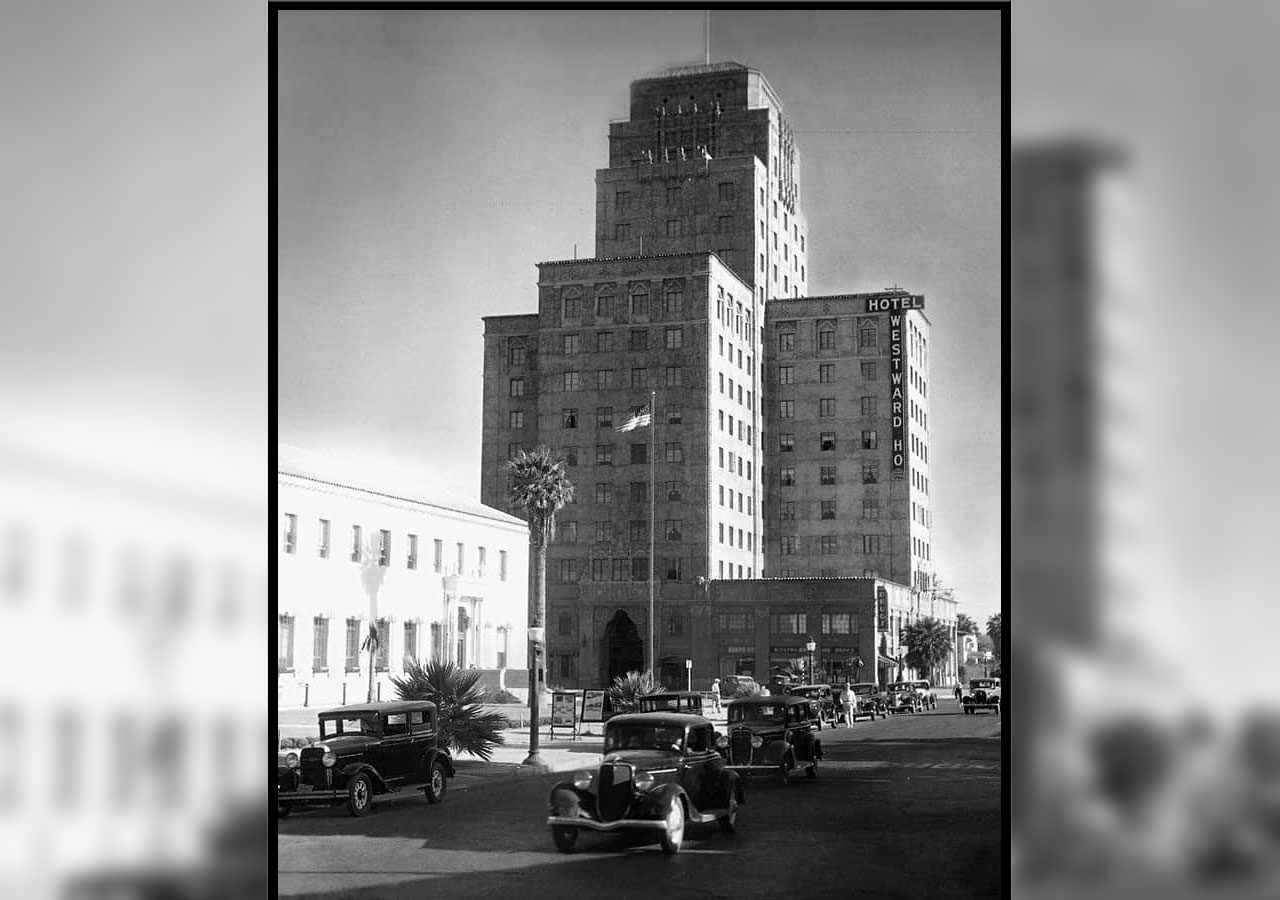

Hotel Westward Ho in the 1930s (Photo: McCulloch Brothers Inc. | Arizona State University Libraries)

Phoenix investor George L. Johnson took over the project and opened it as the Hotel Westward Ho in 1928. The hotel was the tallest building in Phoenix for 32 years.

As a first-class hotel charging $2 per night, at a time when most Phoenix hotel rooms cost a quarter, the Westward Ho was a glamorous hotspot for Hollywood celebrities, powerful politicians, wealthy visitors, and ordinary folk celebrating special occasions.

Guests at the Hotel Westward Ho in 1937 (Photo: McCulloch Brothers Inc. | Arizona State University Libraries)

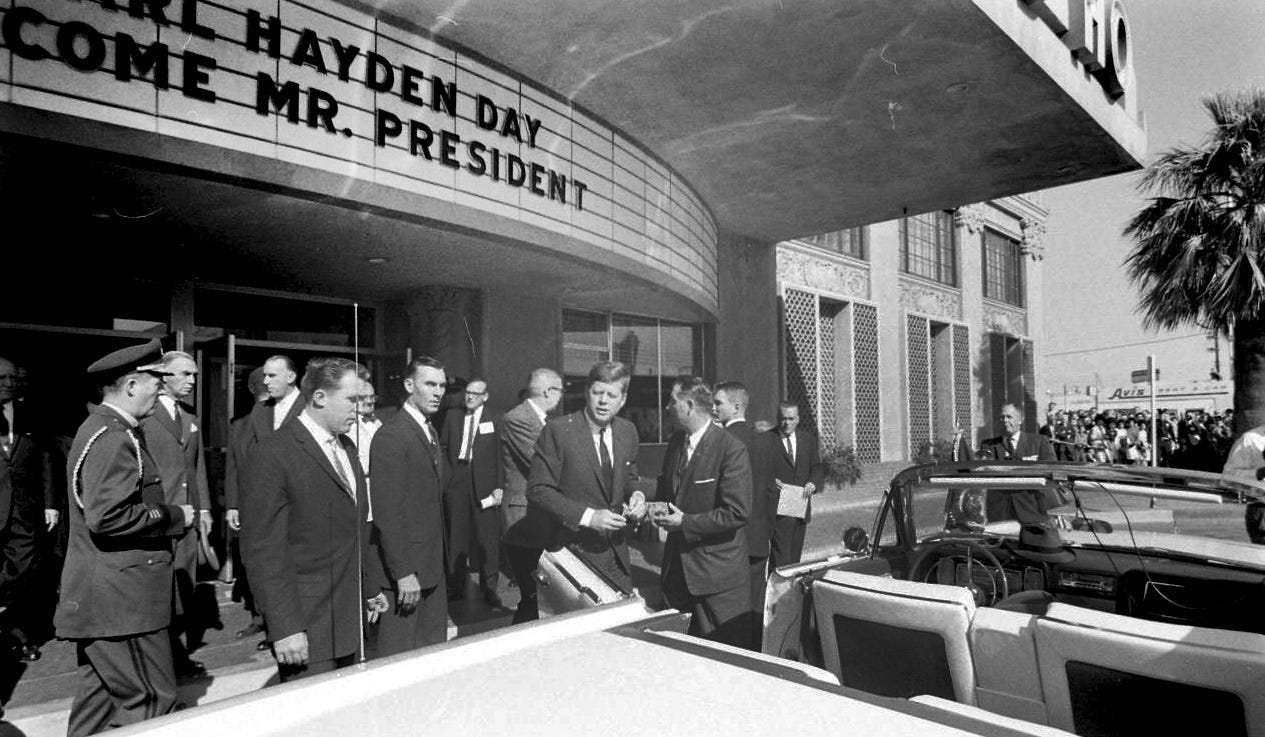

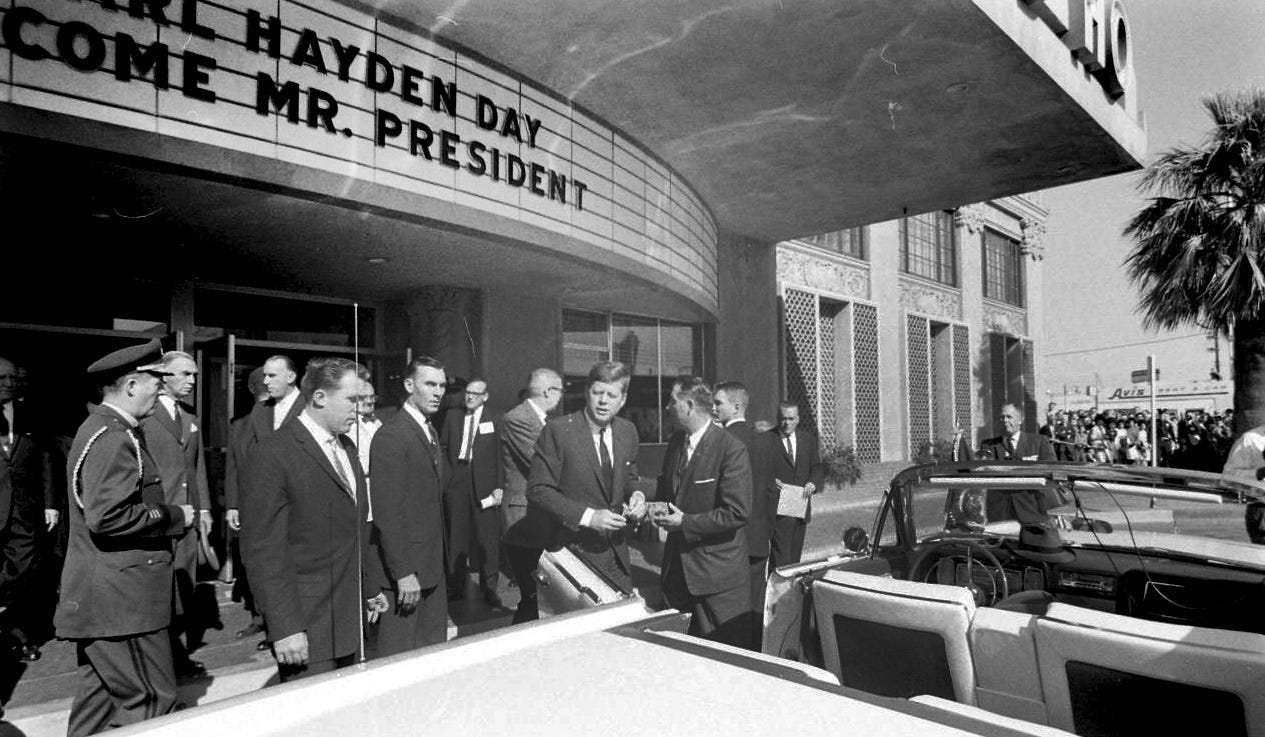

The hotel’s legendary moments include an alleged late-night skinny dip by Marilyn Monroe, and a speech given on its front steps by John F. Kennedy – just days before being elected the 35th President in 1960.

The Westward Ho was also home to Arizona’s first television station, KPHO-TV5. The station used the 268-foot-high television tower atop the building from 1949 until 1960 when a new transmitter was built on South Mountain.

President John F. Kennedy at the Hotel Westward Ho, 1961. (Photo: “The Arizona Republic” | Gannett)

The tower remains an indelible city signpost and is often mistaken for the one shown in the opening of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 movie, Psycho. That famous, now-removed radio tower was a few blocks south, atop the Heard Building. The Westward Ho’s tower did appear in the film’s 1998 remake.

What’s a historic building without a bit of mystery? The hotel used to have a secret tunnel that led east to the long-defunct underground bowling alley, the Gold Spot. There’s even an urban legend that Al Capone’s car lies abandoned in the tunnel.

The construction of the hotel helped solve one of the city’s most vexing transportation problems. The Old Town Ditch, also known as Swilling’s Ditch, flowed alongside Van Buren Street near Central Avenue. The open trench proved to be a magnet for wayward autos.

The Westward Ho lobby ceiling, 2017. (Photo: Danny Upshaw)

The Salt River Water Users Association, now called the Salt River Project, agreed to abandon the canal and divert its water into the Grand Canal in 1923. Three years later, the Old Town Ditch was filled with soil excavated from the hotel construction site.

The Maltese cross-shaped building is a survivor. After World War II when commercial activity shifted from downtown to new suburbs, the Westward Ho stayed in business until 1979. Shortly afterward, the building reopened as low-income apartments for the elderly and disabled.

The Westward Ho on a rainy day in 2018. (Photo: Danny Upshaw)

In 2016, Arizona State University’s social and health services program created a partnership with the building’s current ownership, CDG-PAG. Through this collaboration, ASU operates a ground-floor clinic providing supportive services to the building’s residents.

Today, Phoenix’s skyline—and history—would seem incomplete without its towering presence.

About the author: Freelance writer, hydrologist, historian and artist, Douglas C. Towne first toured the Westward Ho’s ornate lobby during the third annual Art Detour art walk in 1991. It was used as a pop-up gallery, but is not typically open to the public.

The author next to a model of the Westward Ho, 2017. (Photo: Douglas C. Towne)