Verde Park, located just east of Downtown Phoenix along Van Buren Street in the Garfield Historic District, once provided the city with much more than just a recreation outlet. The site was formerly Phoenix’s waterworks that supplied the city with water from the Verde River.

The water project, built in the early 1920s, was Phoenix’s largest public works project and became the city’s first financial boondoggle. “The resulting scandal rocked a couple of city administrations, and at least one public official wound up in jail,” declared a 1954 article in The Arizona Republic. So how could providing freshwater leave such a sour taste in the mouths of residents?

The city’s water system began when Phoenix Water Company, a private enterprise, drilled shallow wells at the site of Verde Park in 1889. The slightly salty water was distributed to the city’s 3,000 residents, most of whom had previously used untreated canal water for their household needs. The city purchased the water company for $150,000 in 1907.

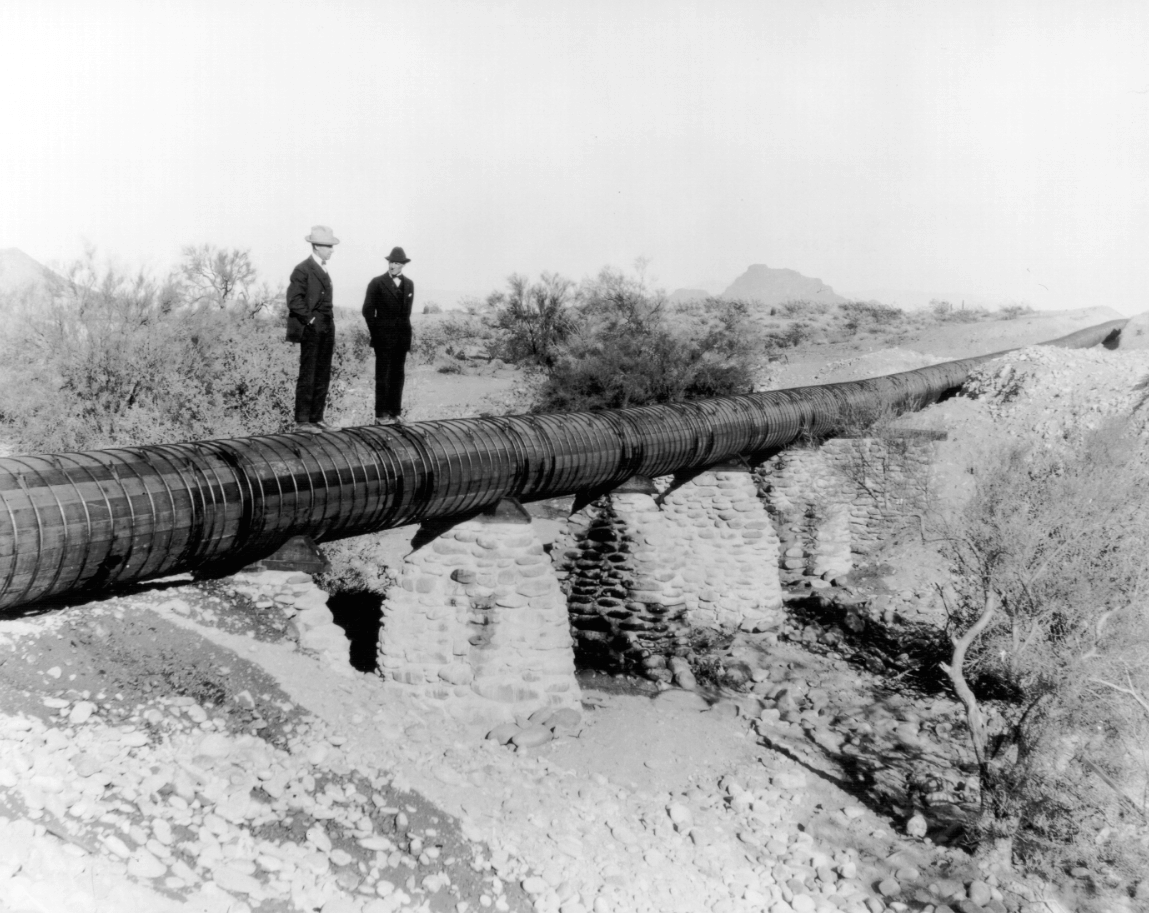

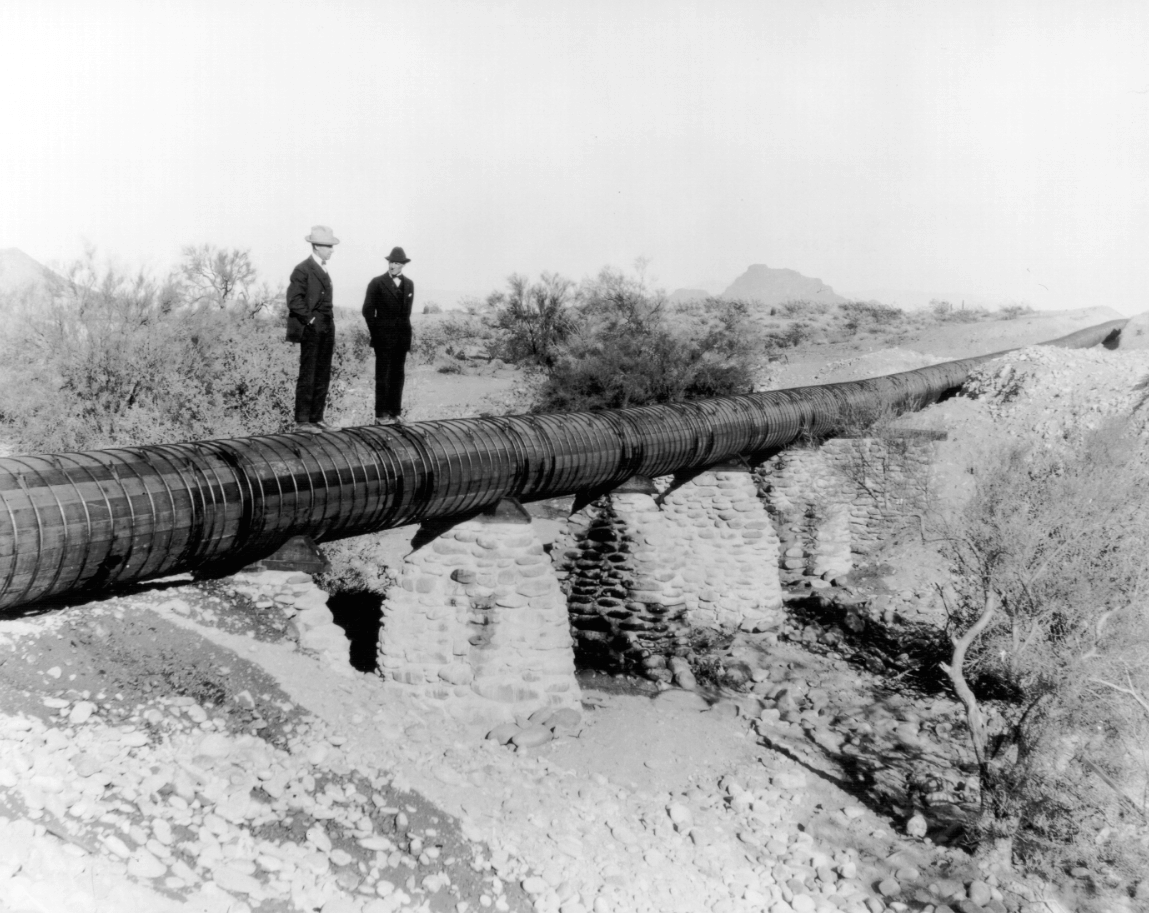

Phoenix’s redwood pipeline, 1920. (Photo: City of Phoenix)

To improve water quality for its residents, Phoenix sought to tap the Verde River above its confluence with the Salt River on Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation lands. Residents loved the idea and approved a $1.3 million bond to construct a delivery system in 1919. But inflation and a shortage of materials caused by World War I rendered the original budget insufficient.

Concrete and metal pipe were too expensive, so redwood slats held in a tube shape by iron bands were used to construct the pipeline. The resulting 29-mile, 36-inch-diameter pipeline went south to the Granite Reef Dam, then followed the Arizona Canal bank road to Thomas Road and continued to Phoenix. Verde River water reached Phoenix in 1921. A chlorination plant was built, and residents could use the water a few months later. Other problems, however, could not be fixed so easily.

“The pipeline wandered over the top of the desert like a snake, sometimes underground, and sometimes on top,” according to a 1954 Republic article. “When someone wanted water, they just knocked a hole in it. It was just a bunch of boards, with barrel hoops around it, so it didn’t last very long.”

Verde Park, 2022. (Photo: Doug Towne)

Within four years, the redwood pipeline was leaking severely. In addition, the project’s proposed 25-million-gallon reservoir, canceled in a cost-cutting measure, contributed to the city’s water supply problems. Without available storage, the water system couldn’t provide constant pressure. Finally, a crisis occurred when a section of a pipeline blew out and sent a geyser of water 100 feet into the air, wasting millions of gallons of water and creating a vast sea of mud in 1930.

The accompanying water shortages influenced voters to approve a concrete pipeline. The new conveyance was completed in 1931, providing Phoenix with a reliable water source.

The redwood pipeline was an engineering failure, which may have been precipitated by grafts associated with public officials. “A lot of money was supposed to have been diverted by very intricate means, and a lot of people left town in a hurry,” one resident told the Republic. “But there was little prosecution. Just stink.”