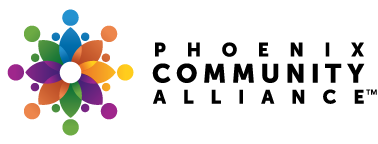

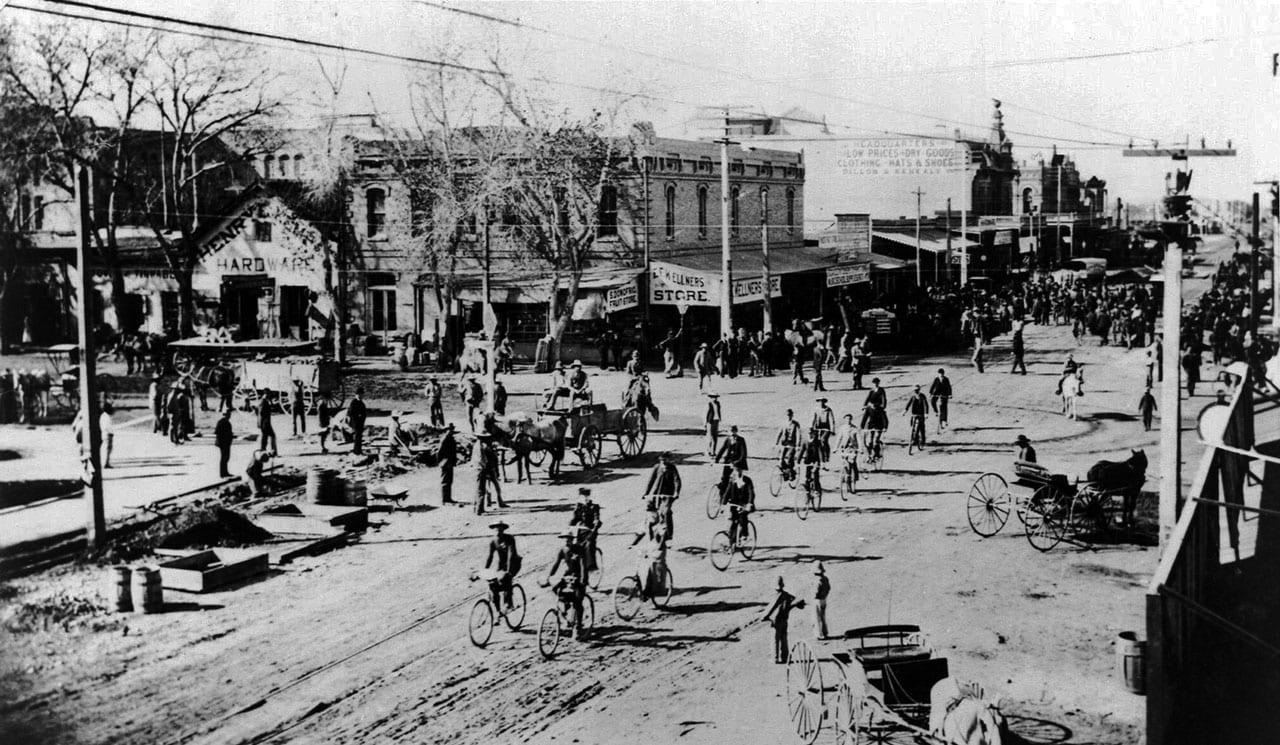

Walking, biking and catching a mule-drawn trolley were regular modes of downtown transportation in the late 1800s. (Photo: City of Phoenix)

Light rail wasn’t Phoenix’s first use of the tracks for mass transit. And those old tracks periodically are rediscovered in some areas of that original system. Mule-drawn trolley cars in Downtown Phoenix date all the way back to 1887, and the debate on how the system should be operated go back nearly as far.

In 1927, the City of Phoenix planned to issue bonds valued at $750,000 so it could upgrade the recently-purchased streetcar system, formerly owned by Sherman Investment Company.

Sherman Investment could no longer adequately maintain the system, which was quite extensive, operating at a loss, and definitely showing its age. But the city council felt that it was important to keep the system in operation for the good of the community.

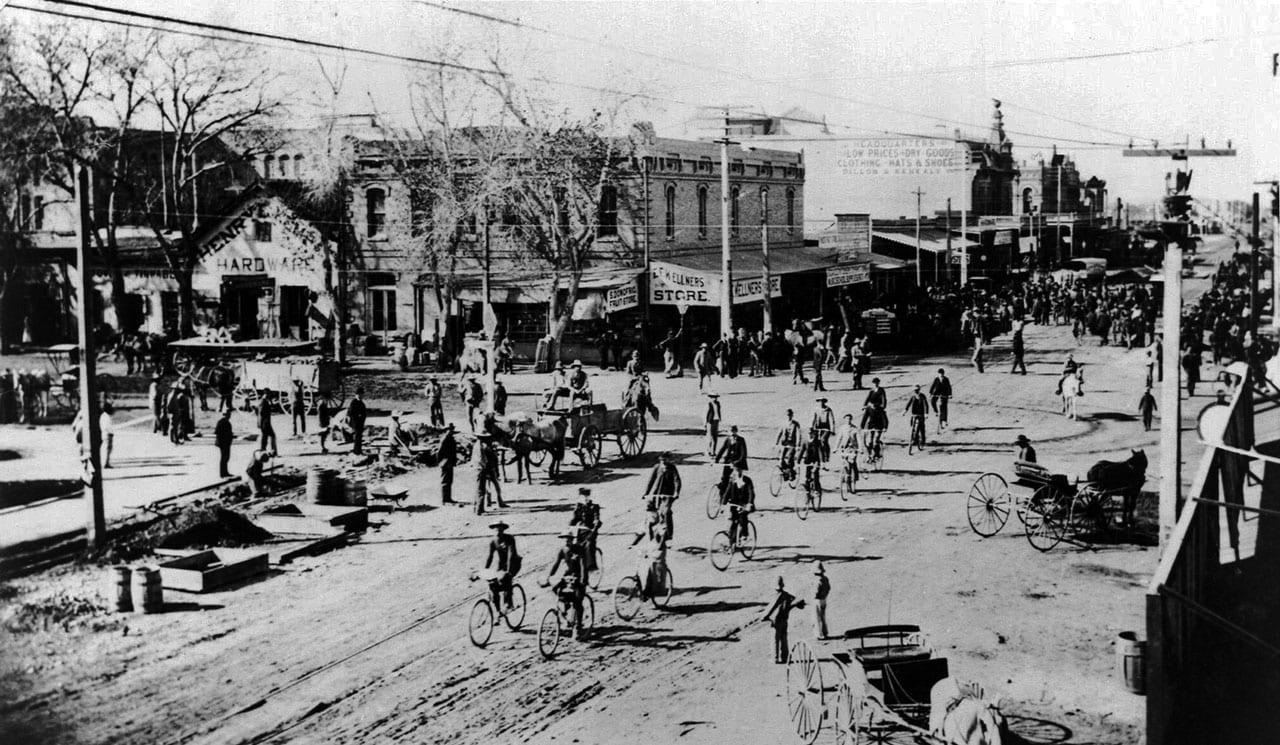

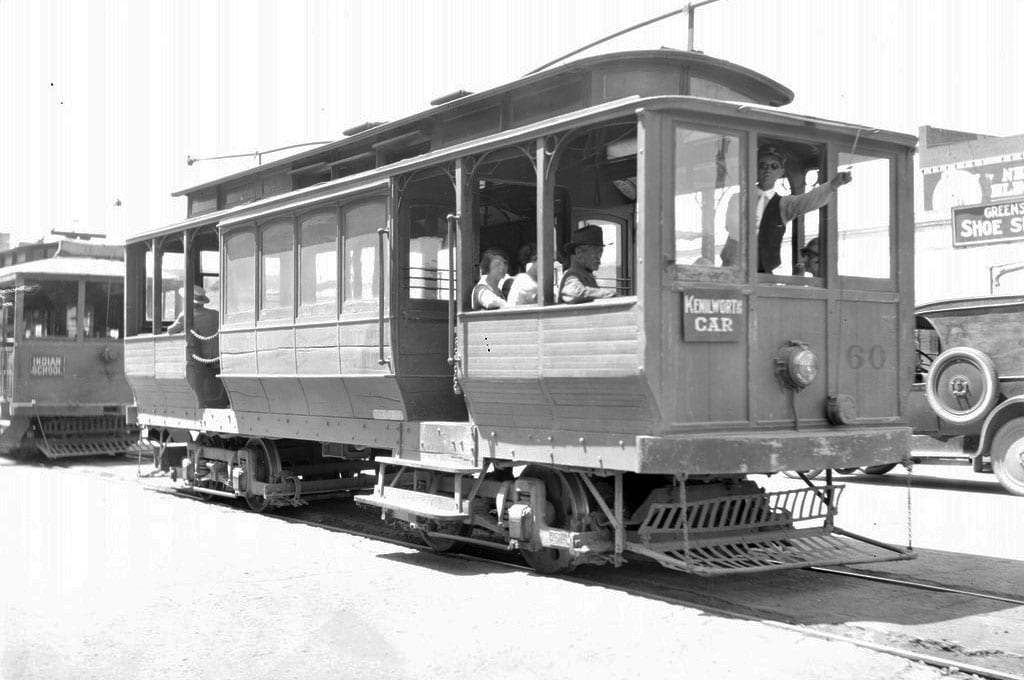

A streetcar in Downtown Phoenix, pictured in 1945. (Photo: McCulloch Brothers Inc. / Arizona State University)

Of course not everyone thought this was a good idea. While the council had announced what was going to be done, at least one citizen decided to sue to prohibit the election for approving the sale. While that suit worked the courts, the election was delayed. After that issue was settled, another suit came forward.

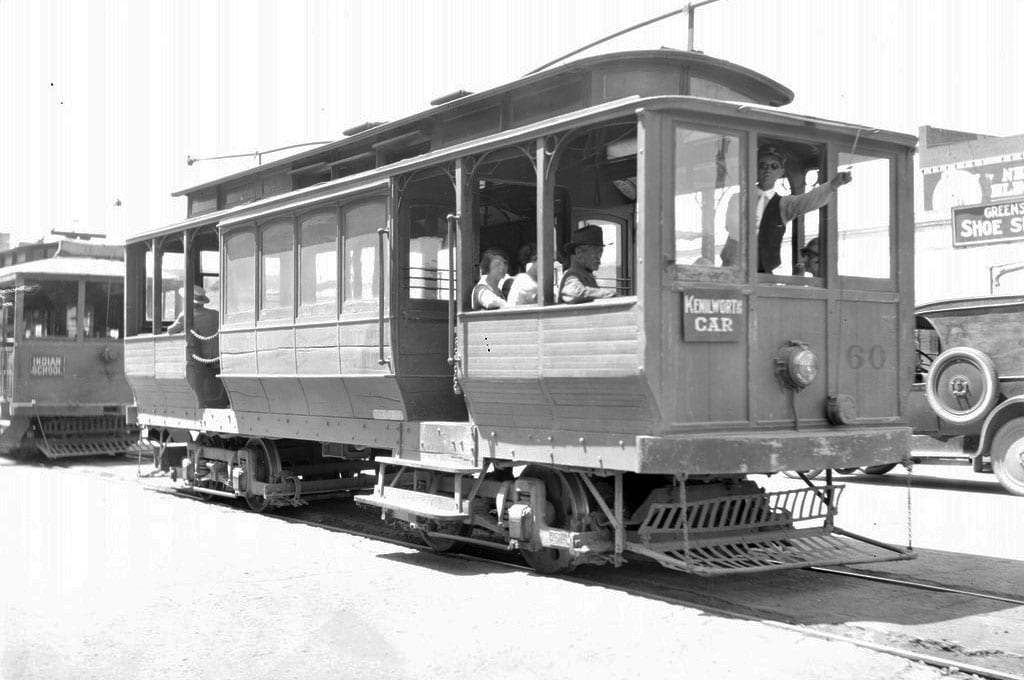

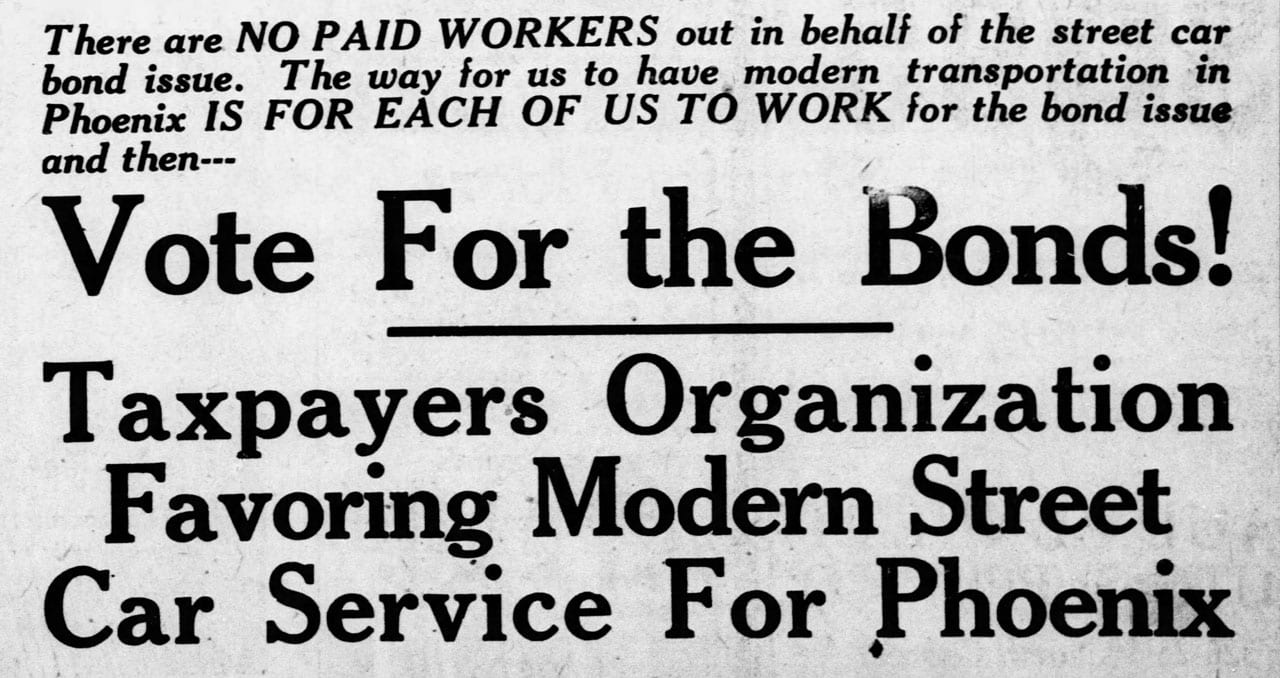

Newspaper columns spelled out the views of opponents and proponents, often on the same page. The proponents argued that maintaining a streetcar system would help relieve the downtown parking issue. The bonds would also provide important items such as new tracks, new roadbeds, and new trolley lines without raising taxes. Furthermore, if the people voted “yes,” it would help Phoenix truly be “a modern metropolitan city,” because a modern streetcar system was essential to the city’s growth.

Those against the City taking over the aging streetcar system pointed out that other city-owned streetcar systems were not profitable, and the Phoenix system did not service the entire community. Furthermore, the money from the bonds could be better spent on other public improvements, because this current system would simply never be a complete transportation system.

The Kenilworth Line, pictured in 1927, ran south from Encanto Boulevard along Fifth Avenue, past the Kenilworth School, and terminated at Second Avenue and Washington Street. (Photo: McCulloch Brothers Inc. / Arizona State University)

At the same time these arguments for and against the streetcar bonds were going on, there was also the issue of a bus line being added. Some even suggested that the opponents of the streetcar bonds and the system itself were actually lobbying for the bus line. But those opposed to a bus line felt it would cost more for people to use it, and would not be as reliable as the streetcars. Both options proved to break down from time to time.

In 1927, the citizens of Phoenix approved the sale of the streetcar bonds. By 1930, the streetcar and bus lines were both operating at a loss. In order to solve this problem, the fare was raised seven cents. In today’s dollars, that would be a little over a one dollar increase. It’s not clear whether that helped make the system self-sustaining, but the papers published the profits every month during 1930.

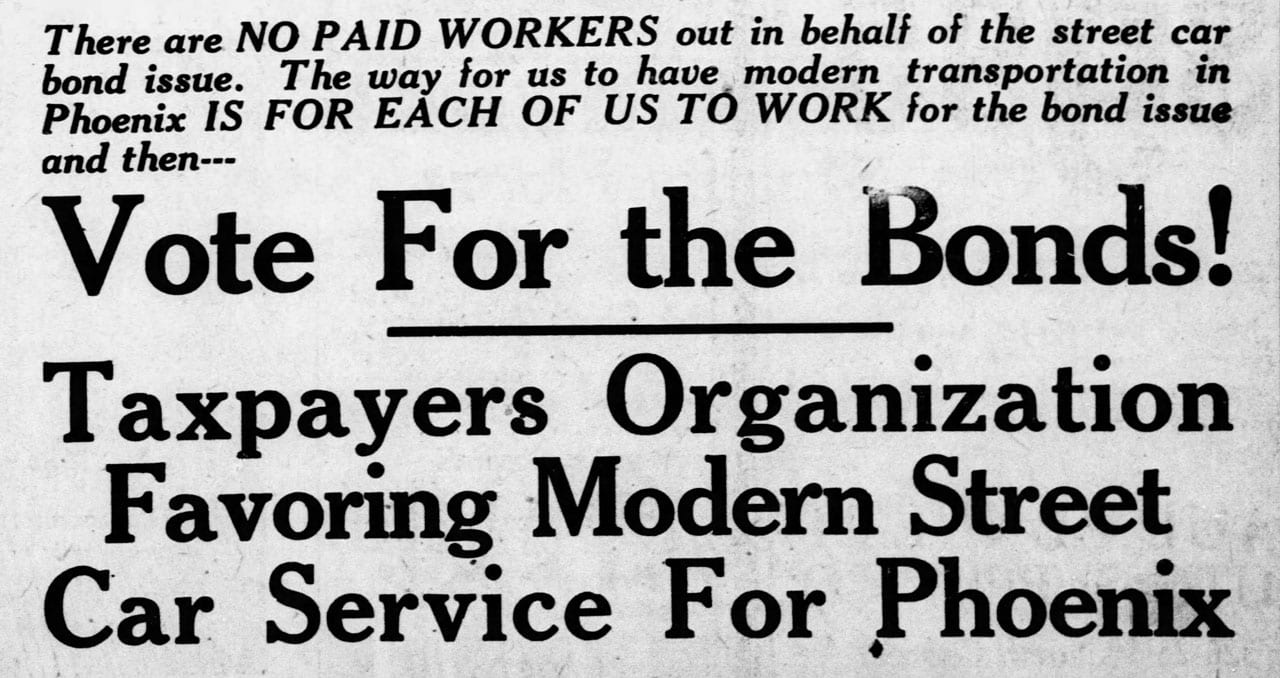

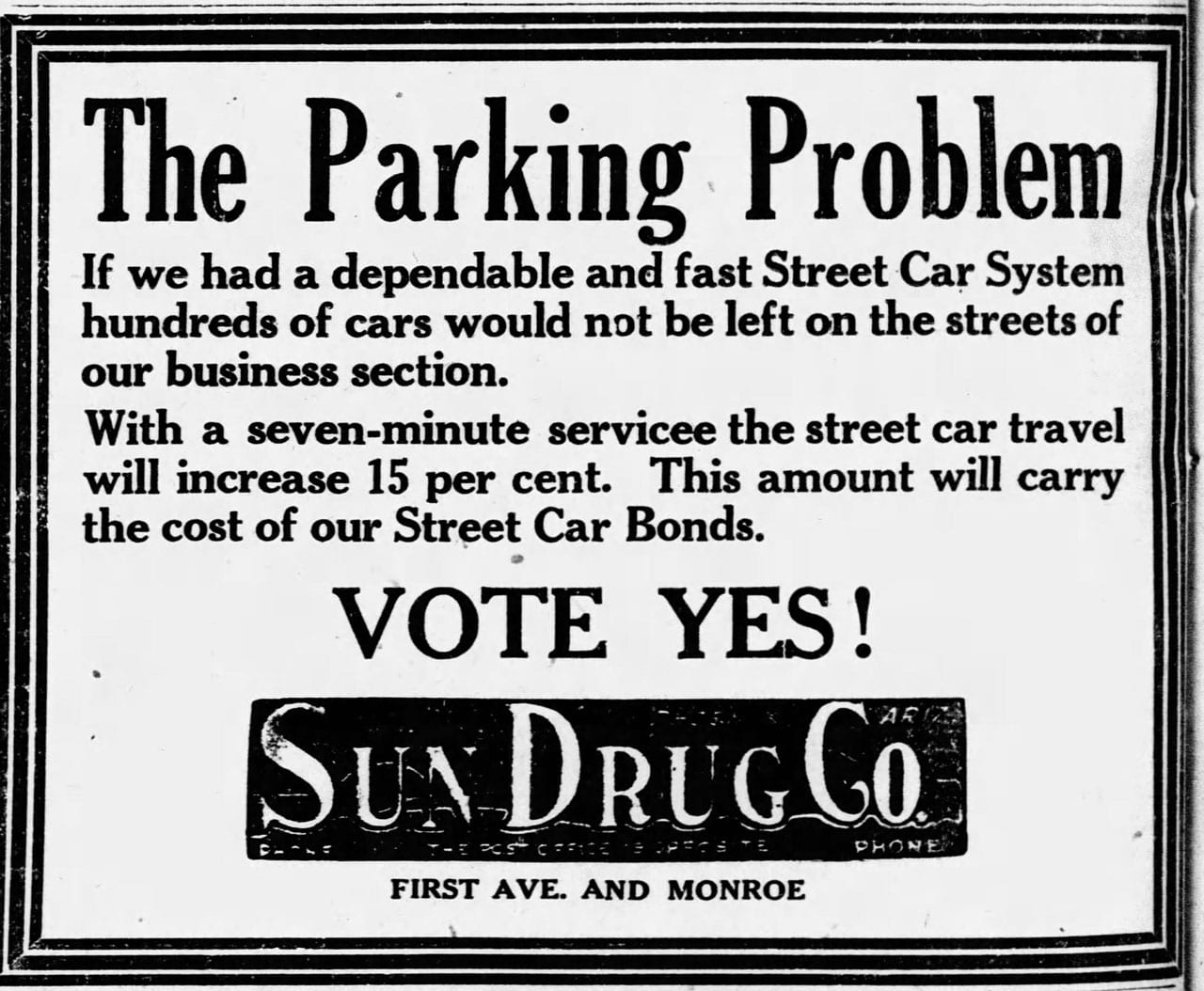

An ad from “The Arizona Republican,” dated April 27, 1927. (Source: Donna Reiner)

Officially, the City disbanded the streetcar system in 1948, although it had been gradually phasing out the various lines. That left the bus line as the sole means of public transit in Phoenix. As the city continued to expand, or perhaps more aptly, explode in growth, transportation was a hot topic. Should we have more freeways, increase the bus lines, or offer some sort of rapid/mass transit?

By the late 1980s, ValTrans rail service was the big issue. Raise taxes to support. Apply for federal monies. Could it be self-sustainable? Would people use it? The pro and con arguments went on and on, not just in Phoenix, but across the Valley. By the way, if you are new to Phoenix and Arizona, ValTrans was voted down more than once and never got off the ground.

In 1993, the regional transportation authority adopted Valley Metro as the name for the regional transit system.

If you have been in Phoenix and downtown long enough, you probably remember the hue and cry over the construction of the original light rail system, and its subsequent extensions. Since 2000, the voters in Phoenix have been asked four times to approve expenditures for light rail, and voted yes every time.

In 2020, Valley Metro ridership topped 52.5 million for bus and light rail.

An ad titled “Let’s All Get the Facts Straight” from “The Arizona Republican,” dated April 28, 1927. (Source: Donna Reiner)

You either love it or hate it, ride it or not. While those of us who live in the West seem as much married to our cars as cell phones, public transit is a vital part of any major city.

As the city embarks on another extension of the light rail system, which will go across the Salt River and into South Phoenix, once again the streets are torn up, and detours are commonplace. If you use public transit, the light rail or the bus, you don’t need to worry as the system will get you to your destination. Okay, you may need to walk a little bit too.

A bus from the Menderson Bus Lines, pictured in1943. (Photo: McCulloch Brothers Inc. / Arizona State University)

As an avid user of public transit (believe it or not, I don’t have a car while living in Phoenix), I let my “chauffeur” do the driving. Bring a good book, pull out your knitting, or listen to some soothing music to occupy your time. But be sure to notice your surroundings, out the windows and other vehicles.

Relax…release the tension of fighting the traffic. We’ve come a long way from that streetcar system the City of Phoenix took over in 1927.

About the author. Donna Reiner has spent more than half her life in Arizona and cannot think of any other place to live. A historian and writer, she’s also a trained classical musician. Car-free since 2016, she uses a huge umbrella to provide her own personal shade while waiting for the bus or light rail.