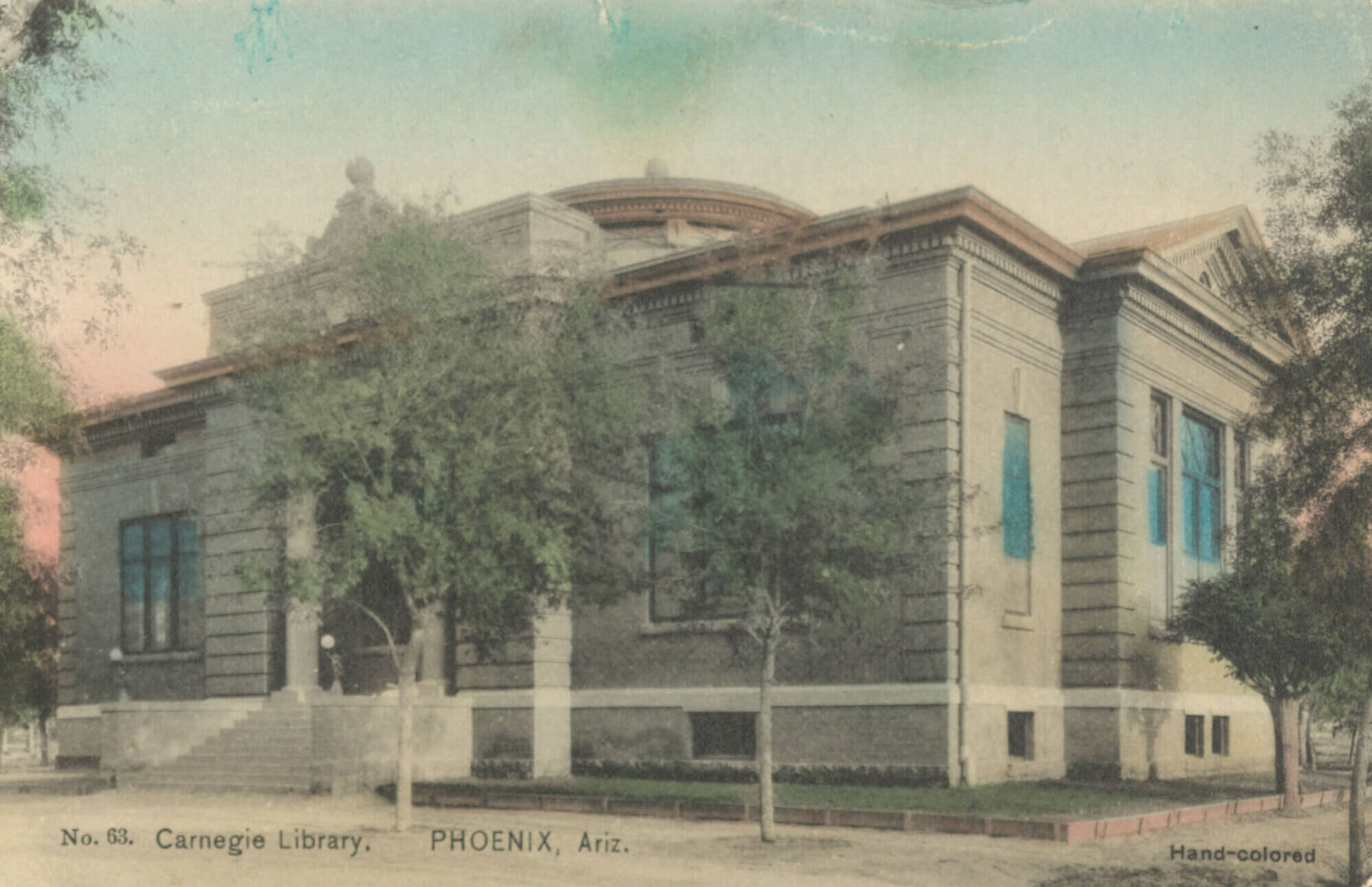

The Building with a Mysterious Zinc-Lined Closet: Phoenix's Carnegie Library

A few blocks west of Downtown Phoenix stands a striking, one-story Beaux-Arts style red brick building surrounded by lush, landscaped grounds. The architectural gem’s impact was far more significant than its modest footprint belies. When it opened in 1908, it was the modern-day equivalent of providing all Phoenix residents with a complimentary smartphone and free internet service.

The Phoenix Carnegie Library was one of 2,509 public libraries worldwide, courtesy of Andrew Carnegie, who financed their construction between 1883 and 1929. Carnegie, an uber-wealthy industrialist and savvy businessman, had a lifelong passion for books. The Scottish immigrant donated money to build the libraries, and the recipient communities were required to supply the property and operational budget. The communities also had to pledge to allow all residents access. Previously, libraries were mostly private institutions supported by subscriptions.

Prior to Carnegie’s generosity, the first public library in Phoenix opened in 1898 on the second floor of the Fleming building at the northwest corner of Washington Street and First Avenue. The following year, it moved to Phoenix City Hall. By 1901, the library contained 1,350 books.

In 1904, the city secured a $25,000 grant from Carnegie. Developer David Neahr donated a 4-acre park as the site for the library building. The property was between 10th and 12th avenues, along West Washington, the east-west boulevard connecting Downtown Phoenix with the Arizona State Capitol.

W.R. Norton was the architect of the building, whose design was later amended by W.H. Reeves and finalized by James M. Creighton. When the library opened in 1908, The Arizona Republican called it “an ornament to the city.” It contained 7,000 books and had a capacity for 8,000 more. The library was centered on the parcel and surrounded by concrete sidewalks. Patrons climbed a staircase on the north side to enter a grand lobby with a circular skylight. The interior had a symmetrical floor plan, oak paneling, plaster walls, hardwood floors, and a coal furnace that provided heat.

The most intriguing aspect of the library was its unique zinc-lined closet, where librarians fumigated returned books for 12 hours before they were reshelved. At the time, circulating materials were considered disease carriers. The disinfection practice was discontinued in the 1920s, and the zinc closet was removed, according to the building’s National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form.

The library’s importance extended beyond its 12-inch-thick walls. The city used the surrounding grounds for horticulture experiments to determine which species thrived locally.

The stately building served the city until a new central library opened at the northeast corner of McDowell Road and Central Avenue in 1952. The Carnegie Library was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974, and architect Gerald A. Doyle was hired to oversee its $1.3 million restoration in 1984. The following year, the state leased the facility.

Since then, the library has been used as a recreation hall, social service center, storage facility, homeless shelter, Arizona Hall of Fame Museum, Arizona State Library Administration and Museum, and Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame.

The building is currently underutilized and likely underappreciated. The Arizona Architecture Foundation hopes to use it as a “Building Archives, Museum, and Library.” That proposed role fits Carnegie’s vision from long ago for the building that had an oversized impact on early Phoenix.